All of the proposed amendments can be implemented without delay. The original Rehabilitation of Offenders Act 1974 was designed as a catch all and passed through parliament in 1974 without an exemptions order for care workers, nurses or taxi drivers etc. etc. etc., so the existing disclosure periods are excessive.

Modern technology including forensic science as well as improved child protection arrangements have allowed the courts to prosecute serious offences more often and to link serial offences more to the same individuals. This has resulted in longer sentencing (due to evidence capture of more crimes) and more appropriate supervision of people with convictions. This would have been impossible in 1974.

With the continuing existence of exclusions and exemptions to the 1974 Act for a wide range of professions and the modern public protection mechanisms from more serious offenders, we broadly agree with all of the proposals to change disclosure periods which have been set out in the proposals.

To allow even shorter and more realistic disclosure periods for most people with convictions would require structural changes within the Act, but we believe that all the proposals are consistent with the requirements for safe and sustainable employment and are suitable as a stop-gap until more robust primary legislation is implemented, which could properly contribute to the rehabilitation of people with convictions.

Further measures to protect and inform employers were implemented in the Police Act (Scotland) 1997, the creation of Disclosure Scotland and the Protecting Vulnerable Groups (Scotland) Act 2007. Combining the availability of this information and the advances in the internet, there has never been a time in history, when so much criminal record information has been available.

With these existing mechanisms as well as the provisions of MAPPA in the Management of Offenders etc (Scotland) Act 2005, the safety nets in the Scottish criminal justice system are robust enough to completely remove criminal record disclosure for work which is not currently defined in the Exclusions and Exemptions Order (Scotland) 2013.

Therefore all convictions could realistically become immediately spent without presenting substantial risk however we concede that the required caveats may be too complex for secondary legislation. This could be unpicked more fully within new primary legislation.

The proposals will allow Scotland to catch up with reforms which were implemented in England and Wales in March 2014. Those reforms are already making a significant contribution to; the performance of welfare to work, tackling poverty, improving public health and promoting a fairer and more equal society in England and Wales.

While these impacts are positive, “rehabilitation” is still omitted from the Rehabilitation of Offenders Act, in that individuals who have not been reconvicted within their rehabilitation period could not reasonably still be described as ‘offenders’ and even if the proposals are implemented in full, the Act will still offer no protection for people with unspent convictions. This means that the proposals offer no immediate benefit or practical incentive to people when they leave prison.

Therefore we welcome an acknowledgement in this consultation paper that a broader consultation for new primary legislation is still required in Scotland as soon as possible.

The new consultation should seek to develop proposals for the following:

• Primary legislation with a title which is fit for purpose, such as the Opportunity to Compete Bill. The title of the 1974 Act conveys negative messages where citizens returning from prison are called “offenders” and it implies that they are not rehabilitated until considerable time periods have elapsed after their conviction. If disclosure is required then these rehabilitation periods would be better described as disclosure periods.

• A process of removing disclosure periods completely or reducing disclosure periods for more serious offences which is based on engagement in services, evidence of changed behaviour, risk benefits and the development of personal resilience. Within this there should be a presumption that nobody who is released from prison should face a lifetime of “disclosure” (or what is commonly described as a “second sentence”) without a process of appeal.

• A review of the exclusions and exceptions to the 1974 act where there is currently no protection for people from discrimination and stigma over very minor and very old convictions.

• The potential of a well designed quota based system where some employers would be required to employ people with unspent convictions. While quota systems are controversial and potentially beyond the powers of the Scottish Parliament, this avenue should at least be open for discussion.

• A requirement for all recruiters (in receipt of disclosure information) to be properly trained to make proportionate decisions and for those recruiters to be empowered and authorised to select a person with a conviction or convictions if they are the right person for the job.

• A right for employers to be supported in risk assessment.

• Measures to consider mitigation of the “Google effect” where failure to ask about criminal history is not the same as avoiding discrimination as well as the complications in managing the confidentiality of spent convictions.

• Addressing the knowledge gap among many key workers about effective pathways to employment for people with convictions.

• Ensuring that all citizens have free, available and accessible information about what and when they need to disclose about their convictions for the purpose of employment. This should include the ability to undertake a check for the purposes of PVG prior to applying for a vocational course for “regulated work”.

• Implementation of Ban the Box processes where any disclosure requirements for the purposes of employment are delayed until after an individual has been selected for interview.

• A statutory right for people with convictions to access specialist support for enhancing skills and finding work which is tailored to their hopes and plans.

• A common sense approach to disclosure of convictions for breaches whereby the current proposals still create disclosure time spans which are excessive.

• Inconsistencies in the information available to employers based on which part of the world that an individual committed their crime. There is no evidence of any risk to employers created by the shortage of criminal history information on foreign nationals.

- Additionally new legislation should seek to specifically find solutions for criminal records intersecting other employment barriers because the stigma of criminal convictions can be worsened for women, people from minority ethnic backgrounds and when the conviction intersects mental health problems. Similarly, conviction labels which include terms such as “racially aggravated” or “domestic” or relate to sex-offending, significantly impede opportunities to compete, even if they are minor offences and sentenced lightly.

This list is by no means exhaustive but highlights some of the limitations to the structure of the 1974 Act to support rehabilitation.

New legislation which supports people with convictions to find and keep meaningful employment, would undoubtedly make critical contributions to Scottish Government policy objectives for health inequalities, diversity, inclusion, poverty, economic development and welfare to work, as well as reducing re-offending.

Findings from Recruit With Conviction action research workshops show that disclosure of even minor criminal conviction can escalate anxiety in the mind of recruiters and this often leads to unfair and unreasonable de-selection. Similarly people with minor convictions often adopt avoidance behaviours when confronted with questions about criminal record disclosure and seek employment in situations where they are not asked, therefore diminishing their own opportunities for suitable employment.

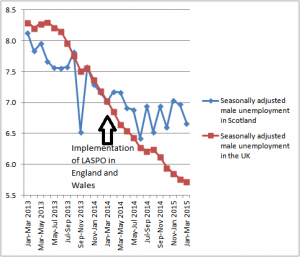

Criminal convictions are most likely to statistically impact male unemployment and by comparing male unemployment trends between Scotland and rUK since the implementation of changes to the Act in rUK, we hope to illustrate potential impacts of reforming the Act.

This graph which was created using data from ONS. It shows a clear trend of Scotland performing ahead of the UK for male unemployment until March 2014 and then lagging behind after Westminster reduced disclosure requirements in England and Wales. This is interesting because it is consistent with Recruit With Conviction findings. Men are 3 times more likely to have a criminal conviction than women and convictions correlate much more closely with unemployed people.

Reports (1) on 31 May 2015 show that Scotland has the lowest female unemployment rate in Europe.

Using big social data like this creates risks for bad social science because causality is rarely able to be defined in correlations. So while this graph neatly illustrates a point, the qualitative evidence and the logic is more compelling and we accept that there are always many competing factors and the policies of targeting resources for female employment in Scotland is another likely contributing factor to the performance of men and women in the Scottish labour market.

It should be noted that while females with criminal convictions are less statistically significant, criminal conviction disclosure for woman is even more stigmatising and previous convictions have greater impact in the labour market for women individually.

(1) http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-scotland-scotland-business-32950469

Recruit With Conviction promotes safe and sustainable employment for people with criminal convictions by working with employers and employability specialists in workshops and ambassador networks. Each workshop aims to both disseminate information as well as inform the knowledgebase about effective practice.

While workshop participants start off with varying degrees of understanding, we strive to respect feelings of participants but challenge misconceived perceptions and promote equality, diversity and inclusion by threading through understanding of unconscious bias about other barriers to employment which are faced by our most vulnerable friends and neighbours.

Please take the time and make your response to the consultation which is available on the link http://www.gov.scot/Publications/2015/05/5592