The name of the 1974 Act as it stands is an oxymoron in that it neither supports “offenders” nor “rehabilitation”. The extreme length of time before convictions become spent mean that no fair minded person could reasonably describe somebody with a spent conviction as an “offender”.

The 1974 Act currently provides no incentive for rehabilitation because convictions become spent automatically, regardless of an individual’s effort to change their lifestyle more quickly.

By excluding prison sentences of over 30 months, the 1974 Act also fails to recognise the human capacity for reform.

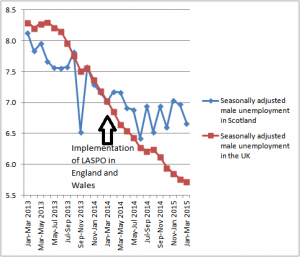

The inflexible “rehabilitation periods” which would be better described as “disclosure periods” are defined only by the court disposal. While the refinements laid out in LASPO 2012 by Westminster are an improvement, they miss the opportunity to provide incentives for reform, rehabilitation and compliance.

LASPO 2012 should be implemented for retrospective offences in Scotland, however the disposal is a very blunt instrument for defining “disclosure periods”.

“Disclosure periods” should be defined the time of sentencing by using LASPO as a guide and adding conditions for completing orders, paying fines and engaging in rehabilitation activities. Additionally a large number of “one-off” summary offences which have no employment relevance should become immediately spent on the proviso that they are a “one-off”. They should also be filtered from any disclosure for positions covered by the 2013 Order.

Similarly for prison sentences where longer “disclosure periods” are defined, the requirement to disclose should be linked with behavioural compliance in prison and be subject to appeal.

The 1974 Act has not accounted for changes in labour demand, recruitment methods, sentence inflation and increased availability of information about criminal histories during the 40 years since inception. While significant improvements have been made to legislation to protect vulnerable groups, the impact of having a conviction labelled as “racially aggravated”, “indecent”, “sexual” or “fire-raising”, exponentially diminish employment opportunities when compared against other convictions with similar disposals or similar risks to an employer.

The decline of manufacturing sectors with unionised protection has changed workplace dynamics and the modern employment landscape dominated by the service sector, has made recruiters more precious about brand. This in turn increases “conviction stereotype anxiety” among recruiters who are typically not trained, empowered or authorised to “recruit with conviction”.

Although Recruit With Conviction promotes honest disclosure processes, the availability of information legislated in the Police Act 1997 and PVG compounds the problem on a practical level. In particular Disclosure Scotland certificates give no contextual information and employers are left to decipher offences and disposals to corroborate a personal letter of disclosure from the individual. This is a burden for employers. Availability of information on the internet has also impacted negatively.

People with convictions have traditionally down-traded their skills and undertaken voluntary work in order to secure employment but current high unemployment has increased competition for such work. The requirement to disclose convictions creates an inequality of opportunity for local people seeking local jobs when competing with economic migrants for whom criminal record histories are less readily available. In contrast, the opportunity for Scots with convictions to escape their past by relocating to London or elsewhere in the UK has been hindered by the Police Act 1997 and the Internet.

Only a small minority of those labelled as “offenders” by the 1974 Act have served a custodial sentence, however parallel statistics from England and Wales (through a MoJ and DWP data linkage project in 2011) show that while 13% of prisoners were in P45 employment in the month before prison, only 5% were in P45 employment in the month after prison. Other evidence shows that most former prisoners, who find work, return to their previous employers. Those who are successful in finding employment, achieve this through their own networks of friends and family, rather than applying for them on the open job market.

The difficulty of finding work in the regular economy underpins labour supply in the illegal labour market which propagates organised crime and abuse by unscrupulous employers such as paying under minimum wage, non-compliance with other employment rights as well as the obvious tax evasion it supports.

Given that approximately 11,000 people were liberated by SPS last year, and that the DWP’s flagship universal work programme has sustained only 80 former prisoners into employment in Scotland (Work programme cumulative job outcomes in Scotland to September 2013), it is a minor miracle that a third of prisoners manage to avoid returning to custody in the 2 years after release, rather than a surprise that 2 thirds of them will return to prison.

The well documented “licence to lie” which the 1974 Act authorises, is absurd. It fails to recognise a job applicant wishing to be truthful and an employer seeking honesty. So the protection should include the way in which a question can be reasonably asked. For example “Do you have any unspent criminal convictions?” can be answered more in good faith while “Do you have a criminal record?” creates a potential obstacle the relationship between prospective employee and employer. Many people who have committed crime in their past, move forward by building trust with absolute integrity and truth. If the question is asked in the wrong way, then they can feel pressured to over disclose.

Over disclosure also occurs when information is not available to the individual or employer.

For the new Act to support access to employment opportunities for people with convictions, it needs to be considered and properly integrated into wider employment legislation and good recruitment practice. Recruit With Conviction is partnering a number of UK organisations to implement “Ban the Box” as policy among private sector employers as a code of practice.

“Ban the box” has been legislated for public sector employers in the USA using slightly different variants in different states. By delaying conviction disclosure to later in the recruitment process more people with convictions will get interview practice, more will get the opportunity to explain their convictions in person and ultimately more will get jobs and keep them. “Ban the Box” also removes the poor practice of pre-selection screening where individuals can be deselected automatically on the grounds of unspent convictions, regardless of their irrelevance to the post and before they can outline their employment attributes.

In Scotland, some public sector employers are currently the trailblazers in good practice with some notable exceptions and in many cases policy and practice are poles apart.

The privilege of exemption from the 1974 Act and outlined in the 2013 Order needs further exploration. It is clear that for the vast majority of people with summary convictions, that these offences are no proxy for future risk and disclosure of such convictions is an unnecessary burden and embarrassment for too many individuals.

It is particularly disappointing that employers in justice agencies such as the Scottish Police Service, Scottish Prison Service and Scottish Court Service appear to have a tendency to almost apply blanket bans (if anecdotal information is accurate). This would be an abuse of their privilege to be exempt from the 1974 Act – although not illegal. Justice agencies should be leaders of good practice because they understand risk, would benefit from the resulting improvement in diversity and could become credible ambassadors for the recruit with conviction concept among other employers.

Failure to “recruit with conviction” is a failure to recruit effectively. Like any cohort of people who are marginalised by a label, “people with convictions” are more likely to need additional support in getting employment but also as a cohort they are more likely to include untapped potential as an opportunity for the employer. For the sake of efficiency and diversity in the public sector, the “recruit with conviction” process should be legislated and encouraged throughout the public sector supply chain as a mandatory community benefit clause element.

Other obstructions to “recruiting with conviction” come from sloppy interpretation of guidance from the Financial Services Authority which invokes regulatory recruitment rules on the Finance Sector, CPNI regulations for recruitment in airports, utilities etc. and HMG Baseline Personnel Security Standards which enforce formal vetting processes for reserved civil service appointments and subcontractors in Scotland. Often these vetting processes are not backed up with credible HR strategies and individuals have been denied employment on the grounds on minor and irrelevant summary convictions. Guidance from FSA, CPNI and HMG Baseline Personnel Security Standards do not enforce blanket bans on people with unspent convictions; however there is a tendency for them to be interpreted very conservatively.

By contrast, the guidance for PVG is relatively clear although time periods for clearance and appeal can be excessive for some individuals. In caring and healthcare settings in Scotland, there has been an improvement in realistic assessment on the relevance of criminal records.

Significant reform is required and legislation is only one of the tools to achieve this. While the Recruit With Conviction campaign has been effective in promoting good recruitment and employability practice, the organisation is a social enterprise which is funded through the sale of workshops and has limited resources.

Employability services are also part of this required reform as standards are inconsistent. Too commonly minimum standards of guidance for criminal record relevance are not met and too often individuals start a course of training or study for work which is incompatible with their criminal record or their willingness to disclose it when spent. Advice to over-disclose spent convictions and advice to disclose non-conviction information occurs needlessly. This is partly due to the complexity of the legislation as well as training needs.

Beyond this, specialist employability services for people with more complex offending histories have become marginalised by commissioning which is reliant on bean counting outcomes rather than promoting assets based approaches to quality support. While the right job for the right person at the right employer at the right time is life changing – the wrong job is a bad outcome.